CONTINUING FOOD CRISIS IN SOUTH SUDAN

Famine averted in localised areas of South Sudan, but unprecedented food insecurity remains.

CONTINUING FOOD CRISIS IN SOUTH SUDAN

Famine averted in localised areas of South Sudan, but unprecedented food insecurity remains.

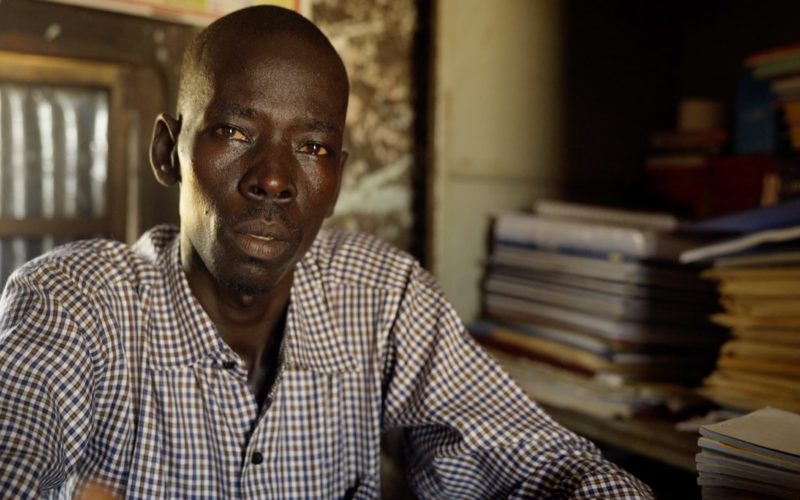

says Catholic Radio Network journalist Alfred Sokia Porfilio from South Sudan, whose station broadcasts anti-war messages. “The country is divided. The politicians fight up there, and we, the ordinary people, suffer.”

Brutal conflict and catastrophic economic mismanagement have devastated South Sudan. Today, the young country is suffering an unprecedented food crisis, with half the population experiencing extreme hunger and around one million children under five severely malnourished. The situation is very fragile. “This conflict has killed many…” says a Jonglei inhabitant who fled home, “children, newborn babies, men and women.”

In February, famine was declared by the UN in Leer and Mayendit counties. Caritas member organisations moved fast to provide emergency relief, getting food aid to 70,000 people in Leer and 52,000 in Mayendit, preventing many deaths from starvation.

Catholic Relief Services (CRS) delivered food aid to over half a million badly hit people in the centre of the country, while CAFOD and Trocaire in Partnership (CTP) and other Caritas members distributed food, water and essential services to displaced people and host communities.

By June, the UN declared that localised famine had been eased, and praised the aid community for its intervention. But with atrocities continuing to rip the country apart, the emergency continues.

According to the latest UN figures there are nearly two million internally displaced people in South Sudan and a further two million who have left as refugees.

Caritas South Sudan and nine international Caritas member organisations are running 54 projects in the country, aiming to reach 684,000 people between July 2017-December 2018, with a combined budget of nearly $23 million. The films that follow take us to visit this work in the field.

“We have been trying to reach the most vulnerable people, but we are not able to help all the affected population.” – Gabriel Yai, Caritas South Sudan

The top priority has been to save lives. Dioceses have opened the gates of church compounds to thousands of terrified people fleeing from conflict – 22,000 in Yei, Torit, Wau and Juba – while Caritas is assisting the relief effort in huge camps for internally displaced people (IDPs).

At Mangateen camp in Juba, where Caritas South Sudan is reaching 8,000 people with water and food, exhausted women tell of the violence that drove them to walk hundreds of miles to seek safety.

“Robbers surrounded the area and started killing people,” says a woman from Jonglei state, whose husband was shot in front of her. “So I had to run with my children.

“We had to escape to save our lives.”

A mother cradles a child with a bullet wound, and thinks back to how things used to be. “Life in Duk was good. We had our homes, we farmed, had cattle and we fished. Now our cattle have been stolen and our houses burned down. No-one lives there anymore.”

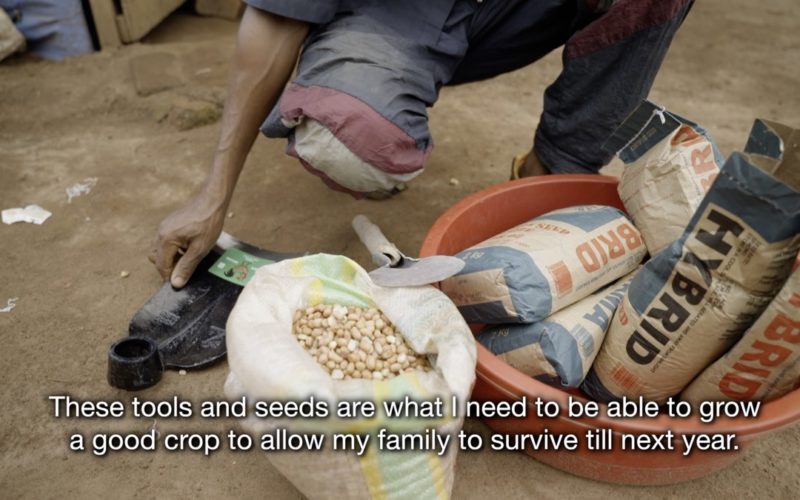

Deprived of their livelihoods, displaced people like these are largely reliant on food aid. But at camps in the Catholic diocese of Tombura-Yambio and in Awerial, Lakes State, farmers are receiving support in an effort to re-start crop production.

In Rii-Menze camp, Victor Nyoko, humanitarian response manager for the diocese, hopes a recent lull in fighting means farmers can grow crops near the camp, and perhaps even return home.

“They are getting the land ready for the second planting season, so giving them these seeds and tools today will enable them to immediately plant… There is life coming back to Rii-Menze now.”

The diocese has a long history of standing alongside the population throughout times when armed conflict and massive civilian displacement have prevailed. Often it has carried on alone, when humanitarian agencies have had to pull out.

“It’s work that we do to save lives,” says Victor simply.

“They really know that the Church is not only concerned about their pastoral needs, or their spiritual needs, but that we are also concerned about their wellbeing.”

All Caritas agencies work to make communities more fundamentally self-reliant. In Awerial, CRS field agents are training farmers in a group approach where people farm together. This means a better yield, as one farmer says: “When we harvest the crops of this farm we will be able to help the whole community. No-one will go hungry here – thanks to CRS.”

Since 2015, CRS have trained 75 field agents and formed 172 farmers’ groups. CTP meanwhile are working with communities on long-term livelihood projects such as poultry production, bee keeping, and improving goat breeds, and are distributing seeds and tools to 4,000 people here in Lakes State.

“The best thing,” says Daniel Achiek of CRS, “is when the community are harvesting – you see the joy in their hearts, and also in their faces. By the end of the project…the community is going to be resilient.”

Such resilience is essential, given the troubled history of this country and its uncertain climate. Caritas members are helping people prepare for future disasters, with savings groups, crop storage, livestock management and borehole maintenance.

Disease prevention is a critical part of this training. A recent cholera outbreak killed hundreds of people living on the Nile in Awerial. CRS quickly moved more staff into the area, with health promoters distributing soap, water treatment pills and equipment, along with information about good hygiene and safe water. CTP also works closely with households on how to reduce risk.

CRS has trained 130 local people as health and hygiene promoters over the last two years, so that lessons learned stay with the community – in Awerial and Juba the message has reached 78,000 people. Across the work of all Caritas organisations in South Sudan, 18% of total budget is being spent on water, sanitation and hygiene, to reduce disease outbreaks.

Cholera cases have dropped rapidly. As farmer Mabinra James says, “The training helped us to look after our family and our homestead. It saved us and the children from getting cholera.”

Ongoing fighting between government forces and opposition groups is not only driving the food crisis but stopping many other normal activities. Keeping schools running is a big priority for the Catholic Church, a major player in the country’s education sector.

The Archdiocese of Juba, supported by Caritas members including CTP, CRS and Caritas Norway, has nearly 12,000 pupils in its schools. Caritas funds books, uniforms and fees, especially for girls; latrine building, clean water supplies and teacher training.

Caring for schoolchildren in a conflict zone is no simple task. Patricia, a pupil at Ss Peter and Paul primary in Juba, tells how students had to walk over dead bodies to get to class. Archdiocesan education coordinator Fr. David Tombe Leonardo stands in a compound where children play. “Behind me there are mass graves of people who were shot around here last year,” he says.

Peace is what these children need, if they are to have a future where there are no mass graves alongside schoolyards. “Once we have peace… people can start living ordinary life, normal life, which every human being deserves,” says Mugove Chakurira of CTP.

In an extremely fraught situation, Caritas members are working with the South Sudan Council of Churches across the country for peace, promoting human rights, conflict resolution and reconciliation. CTP is teaching young people about children’s rights, and CRS is bringing young people into peace processes.

Peace and education, Fr. David teaches the children, are closely interconnected. “Education is our hope for the future and we want to tell our young generation to forget the past, and let us forgive one another.” Or as Paride Taban, Bishop Emeritus of Torit told the young people of South Sudan in a recent radio broadcast, “Hold on to your dreams.”